Of the many things Europe does well, it’s the continent’s magnificent Christmas festivities that can charm any cynical traveler. From Scotland to Switzerland a spirit of festivity can be felt in the wintertime air. The traditions of the season are still strong in this thoroughly modern part of the world, where bustling Christmas markets fill the main square of big cities and bucolic, half-timbered villages alike. In the cathedrals, choirs singing the great medieval Christmas hymns fill the cavernous spaces with angelic harmonies, their melodies carried to the rafters on frosty puffs of breath.

One of the most interesting aspects of Europe is the subtle variations to each country’s celebratory traditions. I find them fascinating. Here’s a sampling of those variations from three different cultures: The German, French and English traditions.

Germany, despite being a progressive powerhouse not known for sentimentality, is actually one of the most magical places to experience the season. Old traditions die hard and Germany reaches far into its medieval past to embrace and celebrate the season. From the Bavaria to the Baltic, from the Black Forrest to Berlin, its people break out the gingerbread recipes, the carols, and the colors of the season.

Christmas Market in Germany

Performances of the Nutcracker are to be found in theatres across the country, while well-built manger scenes adorn the cobbled public spaces of both the Catholic South and Protestant North.

Sprawling Christkindle Markets fill the squares of communities across the country, bursting with music and food and seasonal décor. Traditional favorites such as gingerbread and sweet prune-and-fig candies are served at stalls under a kaleidoscope of Christmas colors. It’s not unusual for a small chorus to be serenading bundled-up shoppers and sightseers with classic Germanic carols.

But the singing of carols is especially beloved and ingrained in the Christmastime traditions of England. In fact, they’ve been a staple of the holiday in England since at least the sixteenth century, as many of the country’s Christmas traditions are. The great cathedrals of Salisbury, Westminster, etc. hold spellbinding choral events by candlelight and colorful outdoor Christmas markets buzz with activity.

Do you like your Christmas tree? Thank England, where the tradition of the Christmas tree originated. The custom originated when pagan-era Druids decorated their places of worship with evergreen trees in the dead of winter, which to them represented life that could not be extinguished despite the cold and the dark. The later Christians appreciated this symbolism, as it reminded them of Christ’s promise of eternal life, and adopted the custom.

The holiday dishes are of course a pivotal aspect of any celebration, and the diversity in food served on the big day is one of the widely most varying customs of Europe’s Christmas celebration. In England the regulars like turkey and veggies are served, but desert is the real treat: The all-important Christmas pudding, a fruity desert usually made with figs and brandy, and mincemeat pies, both fixtures since the sixteenth century.

Another particularly English tradition also includes the wearing of a colorful paper crown—everyone is a king or queen at Christmas. Needless to say there is tea involved on this wintry day as well, often at 6pm on Christmas to warm the soul.

From Bayeux to Arles, France revels in its ancient cultural traditions as it celebrates the Noel with that classically French combination of style and joy. Gift giving is less emphasized than gathering and celebrating simple rituals with family and friends—and sharing a fine meal with good wine, of course.

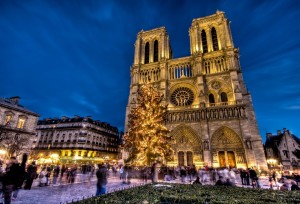

Notre Dame decked out for Christmas.

Paris, the City of Light, celebrates in a less red-and green-light gaudy way than big US cities. But its neighborhoods often host popular Christmas markets that are as festive as any.

In the countryside, where the culture of any people really resides and thrives, the traditions are stronger and richer. The warm tones of local choirs singing medieval carols can be heard emanating from candle-lit, thirteenth-century churches. Many families will attend the midnight Mass and return home to enjoy le réveillon, or the “wake-up!” meal.

And that meal is fantastic. Being France, the food is an integral part of the celebration—in fact it’s the culinary high point of the year for many. Delicacies like foie gras, oysters and escargots are popular aperitifs, while the entrée tends to be more straight-forward dishes like goose (popular in Alsace) and turkey (more popular in Burgundy). Meat (including ham and duck) is paired with a good red wine and served with the ever-popular chestnut stuffing, a French favorite for generations. Chubby truffles are another beloved feature of most dinners. While the use of the actual Yule log has diminished somewhat, the French make a traditional Yule log-shaped cake called the buche de Noel. It’s a sugary delight of chocolate and chestnuts.

After the Mass and le réveillon, the children put their shoes in front of the fireplace hoping that Pere Noel (Father Christmas) will fill them with candy, nuts, fruit and gifts. As the kids drift off to sleep, the adults sit up late, hang goodies from the tree and polish off the Yule log. Before they turn in for the night, a softly burning candle is are left on the table in case the Virgin Mary passes by, a long-standing custom of this Catholic country.